Bold and direct, Gene Luen Yang‘s tale about growing up as a Chinese youth in America works as both an illuminative coming-of-age story and a parable about self-identity. With its multi-pronged approach it delivers a seldom heard point of view without ever coming off as preachy. It’s also woefully short. Spoilers ahead.

There are three stories in American Born Chinese. The first is the legend of the Monkey King and his quest to be respected by the gods and spirits of China. The second is a Perfect Strangers sitcom style homage that follows white American teen Danny and his blatant caricature of a cousin Chin-Kee. The third and central story is that of Jin Wang, his friend Wei-Chen Sun, and their struggles to fit in at school. As the novel draws to a close it’s revealed that all three plots take place in the same universe and are subsequently threaded together. It mostly works, although the introduction of mystical elements into the main storyline is a little jarring at first. We’ll get to that later.

The most immediately obvious thing readers will notice is the unrepentant nature of the subject matter. Being of Chinese heritage, Yang has license to use his culture in any way he sees fit, even if that means steamrolling over politically correct sensibilities. It’s all done ironically with the best intentions in mind, but it’s still kind of startling to see Chin-Kee depicted in the overtly stereotypical manner he is. His appearance, accent, and even name require double takes to comprehend (although the take-out boxes as luggage are a stroke of genius).

The bluntness is a necessary tool Yang uses to explore young Chinese-Americans’ image of themselves and the self-doubt they may experience growing up. Jin spends most of the book in a state of self-loathing, and we learn later that Chin-Kee is a direct externalization of that feeling.

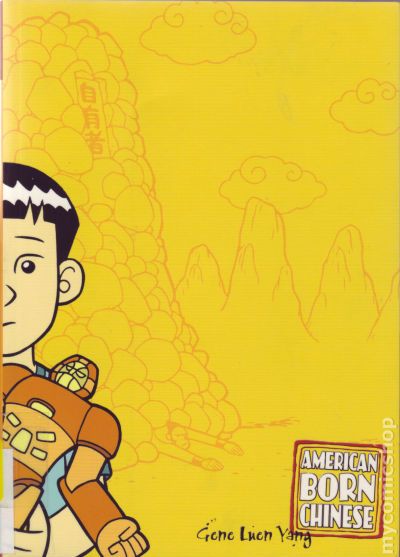

It’s not just the content that’s bold. The artwork is vibrant and strong, with thick lines highly reminiscent of Genndy Tartakovsy‘s work, albeit less angular. Everything is well-defined and clean, making for a visually appealing read all the way through. The fight scenes are a little stiff and could use a little perspective to improve the dynamics, but that’s a minor qualm as they’re not the main focus of the novel.

The only real qualm is the aforementioned brevity of the central story. Jin’s life could use a little more fleshing out, just to add a little more heft to his character’s arc. Each of the three stories could have been their own volume, especially Jin’s misadventures in high school.

Some of the major developments later on also feel a little truncated. It’s revealed towards the end that Chin-Kee is actually the Monkey King in disguise, sent to teach Danny a lesson. Danny is actually Jin transformed through a magic spell, his desire to be white so strong that he becomes Danny. It also turns out that Wei-Chen is the Monkey King’s son sent to guide Jin, only to be disowned by Jin later on.

Yeah, it’s a lot to take in, especially because there’s no hint earlier on that the “realistic” part of the book is tied to the other two. It’s supposed to be the grounded portion that reflects the real world. Then suddenly the transformation from Jin to Danny is hand-waved in a matter of two panels. No explanation!

It’s not too big of a deal, and allows for the reader to realize the clever metaphor Yang’s inserted into the book. Jin might become Danny on the outside, but Chin-Kee haunts him as a projection of his poor self-image. It’s only when Jin accepts his heritage that Chin-Kee disappears.

It may seem a little trite that in the end the message of the novel is “be yourself”, but here it’s the journey rather than the destination that’s meant to draw the reader in. A journey that Yang takes with bold steps, traversing the path both sure-footed and assured.

Final Grade: A-